How the Irish Imagined the Civil War

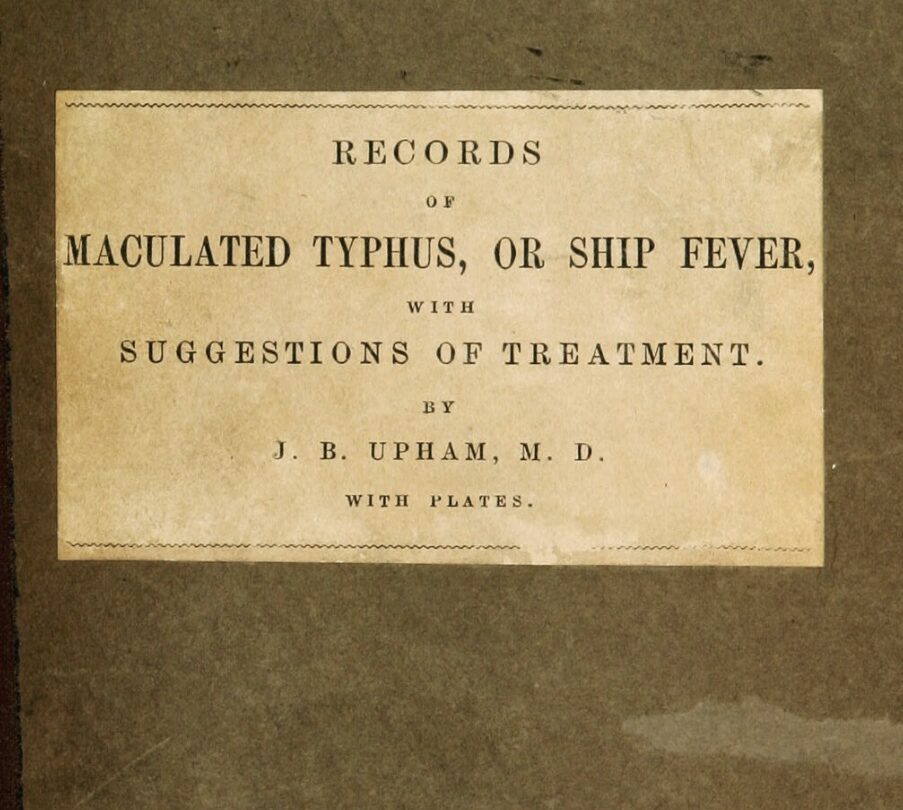

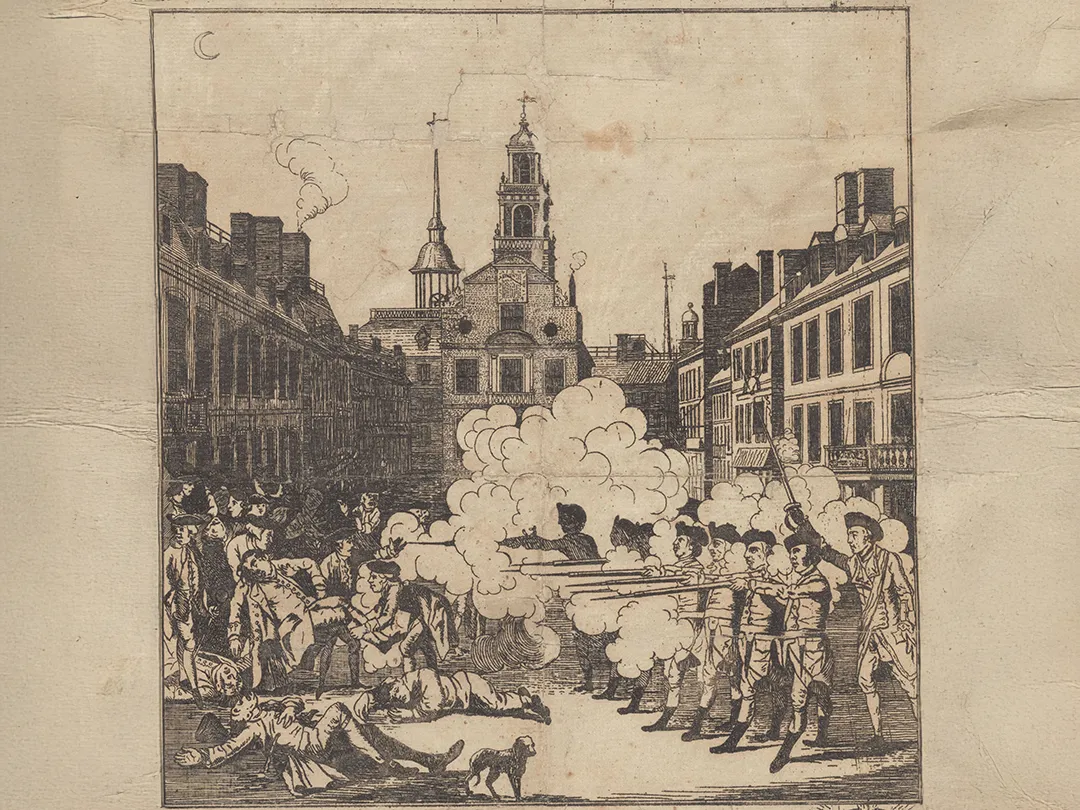

The 150th anniversary of the American Civil War (1861-65) starts in 2011, and organizers across the country hope it will help shape a national consensus – or at least a sincere dialogue – on American values and aspirations.

The anniversary can also be a reminder of how society turns to art to explore grief, conflict and resolution, and how immigrants play a role in shaping the American Dream.

When the Civil War ended, families whose fathers and sons went to the battlefront sought a permanent, tangible expression of their gratitude, grief and pride. Public memorials became those expressions, while serving as symbols for the nation to decipher and reflect upon the democratic ideals for which men fought and died.

Today you’ll still see dozens of Civil War memorials in cities and towns across New England: in town squares, city parks and government buildings. Some retain a central place in daily life, while others are by-passed and overlooked.

A curious sidebar is that many of the sculptors were Irish immigrants.

The Irish excelled in creating war memorials for several reasons. They were stirred to demonstrate patriotism in their adopted homeland, a litmus test of loyalty that all immigrants face. Their sensibilities were shaped by their own centuries-long conflict with the English, and imbued with the notions of valor, honor, pain and loss inevitable in war. While their work captured the power and the glory inherent in battle, it also revealed the humanity of those who did the actual fighting, especially the foot soldier.

Plus, America gave the Irish a freedom of expression that Ireland hadn’t offered, especially to those of modest background and education. The Civil War had “set men’s nature in a universal ferment that stirred sculpture to a greater vitality and sincerity,” wrote art historian Chandler Post.

The Artists

These Irish sculptors included Augustus Saint Gaudens, born in Dublin in 1848 to a French father and Irish mother. His famous work—the Colonel Shaw Memorial—captures the humanity, nobility and utter idealism of war in his depiction of the foot soldiers of the 54th Massachusetts Black Regiment. It is located across from the Massachusetts State House.

Saint Gaudens also created the Admiral David Farragut statue in South Boston, hailed as “the beginning of the American renaissance” in sculpture; statues of Abraham Lincoln (standing and sitting) in Chicago; and General William Sherman at the entrance to New York City’s Central Park.

His younger brother Louis Saint Gaudens assisted Augustus in their Cornish, New Hampshire studio, but Louis was also an outstanding artist in his own right. He is best known for the twin marble lions guarding the foyer of the Boston Public Library’s McKim Building that honors the Massachusetts 22nd Regiment.

Martin Milmore and his four brothers came to Boston from County Sligo with their widowed mother in 1851. They apprenticed to local sculptor Thomas Ball, and their talents were quickly recognized. Martin’s first major piece was the Roxbury Soldiers Memorial (1868) in Forrest Hills Cemetery, followed by the Charlestown Soldiers Memorial (1872) in Winthrop Square.

The masterpiece of Milmore’s career is the Civil War Monument on Boston Common. On the day it was unveiled in 1877, 25,000 Civil War veterans marched on a six-mile promenade through the city to Flagstaff Hill.

Martin’s brother Joseph Milmore was also a noted sculptor, who collaborated with his brother on perhaps the most eclectic Civil War Memorial in New England, the granite Sphinx at Mt. Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge.

Irish-born Launt Thompson built Pittsfield’s Civil War memorial, while the Civil War Memorial in Peabody was modeled after Irish immigrant Thomas Crawford’s Armed Freedom statue that sits atop the US Capital building in Washington, DC. That famous statue was unveiled by President Lincoln in 1863.

Dublin-born Stephen O’Kelly created the Civil War monument in Nashua, NH and three memorials at the Gettysburg National Park in Pennsylvania.

One of the lasting features of great art is its ability to speak to successive generations about the vital issues of the human condition, and in that regard these sculptures have stood the test of time. The Irish influence in the Civil War is permanently etched in these marble, bronze, and granite memorials, which display a sense of purpose, a love of beauty and a desire to shape the collective memory of a nation.

Enjoy articles like this?

Join our mailing list and have the latest sent to your inbox.