Biographies & Profiles

Generations of Irish people have been nurtured, influenced, and elevated by the Irish American Partnership, a Boston-based fundraising group that has carefully invested in education, community development, and peace initiatives across the island of Ireland. To date, the Partnership has raised $63+ Million in support of programs in Ireland since 1986, and their work has…

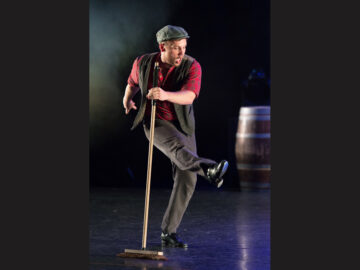

If you want to measure the current vitality and breadth of Irish culture in New England, visit the Irish Cultural Centre of Greater Boston in Canton, Massachusetts any time of year. First opened in 1989, the Irish Cultural Centre is a multi-purpose gathering place for year-round music and dance, learning, seasonal events, sports and socializing….

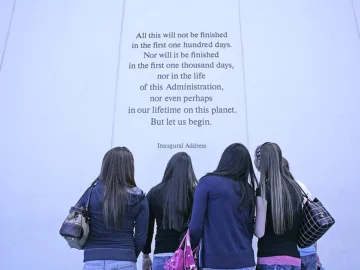

Since it opened in 1979, the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library & Museum at Columbia Point in Dorchester has welcomed millions of visitors from around the world. They come here to be inspired by and to learn more about one of America’s most beloved presidents, Boston native John Fitzgerald Kennedy, the 35th president of the…

Hyannis Port, Cape Cod was a magical haven for President John F. Kennedy and his family, who loved to vacation there and escape the pressures of public life. The John F. Kennedy Hyannis Museum opened in 1992 to keep these fond Kennedy memories alive for visitors and residents alike. Located at 397 Main Street in…

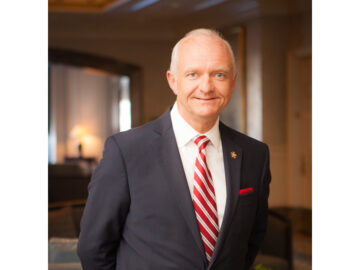

Managing Director & General Manager Stephen Johnston has been a mainstay of Boston’s hotel industry for more than two decades, including 12 years overseeing Boston Harbor Hotel, one of Boston’s most prestigious and renowned properties. Pyramid Global Hospitality, which owns BHH, has created a new position for Stephen in Phoenix, AZ, where he’ll become Task…

General Manager John Murtha is a lifelong veteran of the hospitality industry, including the past 18 years at Boston’s historic Omni Parker House, the longest continuously operating hotel in North America dating back to 1855. He is taking on a new assignment, as Task Force General Manager for Omni Hotels & Resorts. We caught up…

Declan Crowley Congratulations to Declan Crowley on his recent appointment as cultural programming director at the Irish Cultural Centre in Canton. Declan oversees a wide array of cultural and educational activities at the Centre, from live performances and seasonal celebrations to dance workshops and educational classes throughout the year. Originally from Burnt Hills, NY, Declan…

On Wednesday, October 29, the Charitable Irish Society holds its Silver Key Award at the UMass Club in Boston, starting at 6 p.m. The 2026 recipients of the award include Most Rev. Richard G. Henning, Archbishop of Boston and Conor Shapiro, President and CEO of Health Equity International. The annual event serves as a fundraiser to…

Annie Sullivan, known in her life as the Miracle Worker for her work with the blind, especially Helen Keller, was the daughter of impoverished Irish immigrants. Annie was born in Feeding Hills, Massachusetts in 1866. Partially blind herself, she attended the Perkins School for the Blind in South Boston where she learned to read, write and spell. After graduation,…

Cathedral of the Holy Cross in Boston, Photo by Elkus Manfredi Patrick C. Keely (1816-1896), regarded as one of the great neo-Gothic church architects of the 19th century, designed more than 600 churches and 16 cathedrals throughout the United States between 1846-1896. Born in Thurles, County Tipperary on August 9, 1816, Keely was the son…

Boston 26, a non-profit organization responsible for FIFA World Cup 26 tournament preparations and celebrations in the Boston region, has enlisted Meet Boston President & CEO Martha J. Sheridan to join its Honorary Board of notable business leaders, to provide strategic guidance and vision as the region gears up to welcome legions of soccer fans for…

The John F. Kennedy Hyannis Museum on Cape Cod has an exciting new exhibit entitled Paul Ryan’s 1960s, a collection from the acclaimed Boston photographer whose worked captured the zeitgeist of a generation. From Robert Kennedy skiing with family in Sun Valley to jazz legends Dizzy Gillespie and Thelonius Monk at Monterey Jazz Festival, and…

Visitors to the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library & Museum come from all over the world to be inspired and to remember one of America’s most beloved presidents, Boston native John Fitzgerald Kennedy. Open seven days a week from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m., the JFK Library sits on a 10-acre site overlooking Boston Harbor…

The next time you visit Cape Cod, make a special stop at the John F. Kennedy Hyannis Museum. The wonderful museum on bustling Main Street pays homage to President Kennedy and his deep connection to Cape Cod, where he spent magical summers with his parents, siblings and cousins in his youth and later with his…

MARTHA SHERIDANTOURISM TITAN Meet Boston President and CEO Martha Sheridan, recently won the prestigious 2025 ICON Award, presented annually by Boston University School of Hospitality. The award recognized Sheridan as an “Experience Innovator” who creates new and transformative paradigms in hospitality. As a seasoned tourism leader of more than three decades, Sheridan “has reimagined Boston’s…

Irish organizations flourish throughout greater Boston and across New England, with a range of subjects such business and philanthropy, immigration and religion, women’s networking, music and culture, county clubs and sports teams. Here are four of these Irish organizations to know about. Irish American Partnership The Irish American Partnership kicks off its summer season on…

On April 11, 2001, the Parnell Society of Dublin placed a granite marker at the grave site of Ms. Fanny Parnell at Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, honoring her role as a patriot and poet of Ireland. The ceremony was led by Ireland’s ambassador to the United States Sean O hUuiginn, Irish government official Frank Murray and members…

The post-Famine generation of Irish women in Boston and New England were typically relegated to jobs as domestic servants, nursemaids and mill workers, before eventually being accepted as shop clerks, nurses and teachers. This work was often in addition to their primary role running households as wives and mothers. The young Irish girls of the Famine…

The John F. Kennedy Presidential Library & Museum is one of Boston’s most popular destinations, and welcomes local residents, school classes, convention groups and visitors from around the world to come and be inspired. Open seven days a week from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m., the JFK Library sits on a 10-acre site overlooking Boston…

Tourism leader Victoria Cimino has been named as the new president and CEO of Discover Newport, following a robust national search that concluded with a unanimous vote by the Board of Directors. She begins her new role on March 17, 2025. The award-winning destination leader and brand expert, brings over 20 years of hospitality and destination marketing…

Each St. Patrick’s Day season, as Americans ponder how best to honor their Irish heritage in a meaningful way, they often turn to the Irish American Partnership, and for good reason. For nearly 40 years, the Partnership has been helping to ensure that Ireland’s future remains promising by investing in its youth. Since its launch…

The John F. Kennedy Hyannis Museum is the ideal place to learn about the legacy of President Kennedy and his deep connection to Cape Cod, where he spent magical summers with the Kennedy family and with his wife and children. Located on Main Street in downtown Hyannis, the museum has ongoing exhibits such as “Presidential…

On September 2, 2024, The Christa McAuliffe State House Memorial Commission unveiled a Christa McAuliffe statue at the New Hampshire State House in Concord. The dedication took place on what would have been Christa’s 76th birthday, with support from the Governor’s Office and the McAuliffe-Shepard Discovery Center. Photo Courtesy of McAuliffe-Shepard Discovery Center Renowned artist, Benjamin Victor, was selected by…

Acclaimed actress, author, and model Bridget Moynahan is the 2025 recipient of the John F. Kennedy National Award, issued annually by the St. Patrick’s Committee of Holyoke, MA. The prestigious award is bestowed each year to Americans of Irish descent who have distinguished themselves in their chosen career and who demonstrates the values of family, faith and community…

Get the Latest Irish News & Events in Your Inbox

Join our mailing list